- Home

- Meltzer C. Rips

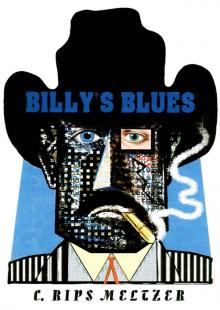

Billy’s Blues Page 3

Billy’s Blues Read online

Page 3

Besides affording me the opportunity to go outside with the proper aura of protection required by the Igbo, my compadres do many other kind things for their amigo gringo. They also sign for the materials I’ve ordered concerning Billy the Kid and the Old Southwest. Such books and videos are usually delivered door to door by UPS men and the like, but I can’t trust interaction with such strangers. As a result, my packages arrive doubly blessed, as long as I can make it to the lobby.

There was a road, north, through the San Agustin Pass that would take them up through Tularosa and to the U.S. Indian Agency. There, they could get an escort through the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation and head through a small town called Lincoln, also the county seat for the Pecos Valley. Billy heard it was the best place to inquire about work, especially for men good with a gun. Tom, however, knew a better route east through the Guadalupe Mountains that would take them into the southern tip of Chisum country near the Texas border where there were lots of paying jobs either working for the New Mexican cattle king or against him. Unknown to Billy, the Guadalupe Mountains were located at the southwestern tip of the Indian Reservation and roving bands of renegade Apaches were known to supplement their meager reservation rations with frequent ambushes along the old Indian trails.21

A safe time to leave the apartment is shortly after 10 a.m. before I go to bed. By then all the ants have crawled out to work and I can safely leave my den. Maids and maintenance crews, often relatives of the doormen, patrol our dim hallways, but they are friendly. It’s best when one addresses them first—¡Buenos días! ¡Buenas tardes! ¿Una Noches Bonito, no?

After over a hundred miles of hard riding, out of food and water, they started climbing an old Indian trail over the Guadalupe Mountains. Spying a pool of water at the bottom of a canyon below them, Billy dismounted and took their only canteen down the cliff to fill it up. While at the bottom he heard gunshots echoing through the canyon. He scrambled up the cliff, but by the time he made it to the top, it was too late. There was no sign of O’Keefe, the horses, or anything, including his bedroll. On foot yet again, Billy stumbled down the mountains as the sun set coldly behind him.22

The crucial consideration, however, is timing. One mustn’t go out during high risk periods of potentially negative encounters. Such times are during morning and evening rush hour. There are also pockets of danger zones during the day. For example: dinner-time delivery boys emanate especially evil ions.

He hid during the day and walked at night. With the mountains descending into arid foothills, the kid grew tired and hungry. Losing the strength to even carry an empty canteen, he threw it away. It was on the third day, no longer caring about the threat of Indians or the heat, that he lay down to rest without realizing he was only a few hundred feet from the Rocky Arroyo river. He lay there in a semi-conscious state unable to move as the sun reached its apex and temperatures soared to 110. Fortunately for the kid, however, a few of Ma’am Jones’ ten children had snuck away to play by the river. They overheard the kid moaning and ran to tell their mother.23

Timing is everything.

Chapter Five

“If you want to hear about the Kid well then I will tell you. When we found him, it looked like he sorted bobcats for a living. After we dragged him inside, I sat him down at the table. When I took off his boots, he moaned like a panther in heat, and I could see his feet were bleeding and swollen. They struck me as rather small like a woman’s and he wore no socks. I offered to wash his feet and put on water to boil. Although it was a warm day, he shivered like a frozen pup, so I wrapped a blanket around his shoulders. I asked when he had eaten last and he said that he had not had any food in three days so I heated him some milk. I will never forget the look of that strange boy sitting at my table hunched over in a blanket with his feet soaking in hot water, his sunburnt face peeling, and his dirty blond hair standing on end like an angry porcupine.

“Still, he did not look no older than my third son, Bill, who at that time was fourteen years old though most said he was big for his age.”24

I relax completely and the unseen force softens its grip. With each attempt to free myself from its grasp, it retightens its hold in kind, so I lay perfectly still. The world within the circle of light emanating from the campfire begins to swirl wildly like the whirlwind in Dante’s second circle of hell. Trees sway at the border as if struggling to hold back the darkness. Leaves spin about the burning logs. Bugs play cat and mouse with flames as sparks leap at the night sky becoming one with the stars above. Grinning, the strange bucktoothed manchild hovers over me.

“When I held out the cup of warm milk for him he said, ‘I don’t like milk.’

“‘Drink it,’ I said. ‘You can have some food later. You will not be fit for eating until you rest a little.’ But he turned away, so I said, ‘Do you want me to hold your nose and pour it down your throat?’ When he took the cup, he made a sour face, but when he started drinking, he drank too quickly so I took the cup away and told him just to sip it. When I told him that I was going to put him to bed he said, ‘I can sleep right here.’ I told him he was worn out and would sleep better in bed. After I helped him to bed, he let me tuck him in.

“He slept all that afternoon and through the night.”25

He removes his poncho and uses it to wrap the rifle before laying it down beside an empty bed roll, unslept in, as if waiting for an occupant. A large pistol rides his hip, holstered to a thick leather belt. A smaller handgun hangs upside down from his neck noosed around the trigger guard. He looks down as if considering whether to wake me. Carefully, he reaches out for my face like a mother feeling for a temperature, but instead of resting his hand on my forehead, he places it over my mouth. With his other hand he holds my nose, making it impossible for me to draw oxygen. Trying to fight, my muscles freeze. As I frantically strain to move, my body begins to vibrate uncontrollably. The harder I fight, the more I reverberate. If I could just move one muscle, a foot, a finger, I could break the spell, reaffirm contact with the physical world, awake from this nightmare of immobility. My heart beats at my chest trying to leap out and suck in air.

“The next day he introduced himself as Billy Bonney. It was the first time that I had ever heard a last name of Bonney and it sounded made up, but we did not ask such questions west of the Pecos. A man’s name was his own business. It was what you did that counted.

“Years later, after Bob Olinger murdered my son John, it was Billy who made Pa keep his promise to me that he would never duel. He also told my son Jim to let him take care of Olinger because my boys were not mixed up in anything and he did not want them to be dragged into the feud. I told Billy that I did not want any of my boys to go after Olinger, and that included Billy. I told him to go away before it was too late, that he was young enough to start a new life somewhere else. ‘It’s already too late,’ he replied.

“When those three killers (Olinger, John Kinney, and Billy Mathews) were assigned to guard Billy on the trip from Sante Fe after his sentencing, I never thought that he would make it back to Lincoln alive.”26

The safest place for a, murderer

is to get a job as a deputy.27

“When they told me about Billy’s escape from the Lincoln County Courthouse, I prayed for J.W. Bell’s soul, but thanked the Lord for having spared my husband and sons, for whether they killed Olinger or Olinger them, their souls would have been the devil’s bargain. If anyone prayed for Olinger, I cannot tell. His own mother, who I know from church, admitted that he was a sinner and murderer of men and had prayed the Lord’s forgiveness for having bore him into the world.

“When I heard that Pat Garrett had shot poor Billy as he backed into Pete Maxwell’s room, I prayed for Billy’s soul, but I did not pray for Pat. When I heard that Pat was shot in the back years later, I knew it was the Lord’s doing: As ye hath sinned, so shall ye be punished.”

- Barbara “Ma’am” Jones28

Lightheaded, darkness overwhelms me, growing blacker and bla

cker, until, unable to struggle anymore, I give in and completely relax to my fate. My unbreathing self melts into the ground and becomes one with the absolute stillness and absence of light, feeling, thought. Then, as suddenly as it began, I’m released and find myself gulping for air, heart pounding, skin cold with sweat, throat too dry to swallow, sucking in air thick with devil’s snow and swirls of Mormon rain, alone, more alone than I could ever imagine feeling before. Then I hear a voice from outside, in the blind distance, coming closer, an aged, pained voice cracking with loneliness and confusion, seeking me, beckoning for me to answer:

“Hello …?”

Chapter Six

The first day of spring. Dull roots, stirred by vernal rains, shake off winter’s icy grip. The air thickens with the smell of last autumn’s leaves rotting in the muddy thaw. A sudden humid warmth unearths lost memories of youth as well as the decomposed debris of human refuse heaped winterlong beneath the frozen crust. Springtime sewers overflow, clogged with months of unswept garbage. Suicides and murder victims rise to the slimy surface of the East River. All the foul smells, once hidden by winter’s odorless frost, now mingle uncomfortably with the scent of lilacs as they reach for the heavens between discarded prophylactics and soiled under-garments. Like lemon-scented ammonia in public toilets, the fragrance of fresh flowers only seduces you into letting your defenses down. All kinds of fearsome bacteria and toxicants flood unfiltered into the overloaded nervous system.

There’s guns across the water aimin’ at ya,

Lawman on your trail he’d like to catch ya,

Bounty hunters too they’d like to get ya,

Billy they don’t like you to be so free.29

When out among the sullied sublunary world, even for a few moments, I can’t wait to return homeward to safety, to the pleasure of scrubbing hands clean whether I was exposed to a soiled coin, a public bannister or just the tainted wind. A foulness breeds freely beneath every surface, on the sweaty palms that reach out to shake your hand, behind every grimy door, every false face masking wickedness and hypocrisy. All hide ugly truths, darkened and diluted beyond recognition.

Billy don’t you turn your back on me.30

The ugly truth is always hidden.

Billy don’t it make you feel so low down,

To be hunted by the man who was your friend.

—Bob Dylan31

Take Billy the Kid: the more one researches, the more one uncovers.

As history books and dime store novels alike tell it, Henry Michael McCarty, alias Billy the Kid, was shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom at Fort Sumner, July 14, 1881.

Beyond this widely accepted fact, however, few are in agreement. To land-grabbing cattle barons, like John Chisum, Billy was both a cattle rustler and a rake who was after both his cows and his beautiful niece, Sallie. To presidential hopefuls like Governor Lew Wallace, author of Ben Hur. William H. Bonney was a thorn in the side of his political ambition. To power-hungry thugs like L.G. Murphy and Jimmy Dolan, the Kid stood in the way of their monopoly over the citizens of Lincoln County. Yet to the Mexican people, uprooted from the land of their forefathers (a land they had so painstakenly wrestled from the Mescalero Apache), El Chivato (the billy goat) was a modern day Robin Hood who stole cows from rich cattle barons (greedy gringos) and generously shared his wealth with the little people (and his seed with the señoritas).

However, to the American public at large (including Washington), fueled by serials like ‘The Forty Thieves’ (which represented Billy as a cold-blooded killer and leader of a ruthless gang), the kid was a threat to civilized society. The ‘Boy Bandit King’ was an untamed beast. After all, those who conduct themselves above the law undermine an American dream founded upon the principles that hard work is rewarded and evil punished all for the good of the community, God, and the nation as a whole. In other words, the individual must earn it fair and square. Is that not democracy?32

I rode a trail through my neighbor’s back yard

Shooting the bad guys through my handle bars.

Known for my bravery both far and near,

Being late for supper was my only fear.33

Yet, what law determines who the most deserving individual is? Natural law? Who, more often than not, reaps the rewards of American democracy: crooks, politicians, the not-so-idle rich? Certainly not the meek. Are not the most worthy often left forgotten, rotting away in dark apartments, knowing too much for their own good, unable to fit into a world of befouled values and morals askewed?34

These days I don’t know whose side to be on.

There’s such a thin line between right and wrong.

I live and learn, do the best I can.

There’s only so much you can do as a man.35

I know I must go out there sooner or later. Provisions are low and I should mount an expedition for supplies, but the timing must be right. Helios is on the rise again after a long night in hiding. I look out the window and watch as the rose fingers of dawn climb the building across the way. With each new window enveloped by sunlight, reflected rays pierce through me, yet I can’t pull my eyes away. Behind each pane, faceless shades ready themselves for day. They’ll be rushing to work soon. Hostile and indifferent spirits will fill the fetid air, waiting to piggyback on the unsuspecting soul.

The sun rises. Lemmings flood the streets. Too late to go out there. Time for bed.

I miss Billy the Kid

The times that he had, the life that he lived.

I guess he must of got caught,

His innocence lost, I wonder where he is.

I miss Billy the Kid.

- Billy Dean36

Yes, bed.

Floating beneath the stars on a cloudless night, my weightless spirit glides above a dark green forest touched lightly by the moon …

Chapter Seven

“Hello …?”

I’m awoken at 5:30 p.m., well before sunset, with a headache among other ills. My eyes hurt from too much dreaming and, while asleep, I somehow sprained an ankle. I sit up, crack neck and back, and draw the curtains open to watch the sun set violet. The streets empty, then fill with lamplight. A few stragglers drag themselves home late to dinners kept warm in the oven. I make out a stick lady struggling, two-fisted, with a puppy on a leash. She snaps the pup’s head back as it noses a passing stranger.

When darkness descends and dinners are served, it’s late enough to venture outside free of identification, late enough to be free of prying commuter eyes, eyes that rise briefly with disdain to gaze upon the unchained, like myself, as the wretched slaves slouch homeward after a day of pointless labor.

The Lincoln County, New Mexico, that Billy the Kid entered in 1877, was a violent and lawless land.37

I dress over my pajamas and stretch on a belt. A baseball cap organizes my hair. Last, but not least, I don a pair of latex examination gloves. I squeeze out of my room into the foyer. Before opening the door, I brace for the smell of the dim, depersonalized hallway. Yes, they vacuum the rug twice a week, but it smells so … peopled. I stand before the door, gloved hand upon the knob. My heart beats. I feel dizzy. I take a deep breath and swing open the gate.

My worst fears are immediately realized. I try to move back, but my weighty momentum has shifted me too far forward. I right myself, but it’s too late. The door shuts loudly behind me. Standing by the elevator, she peers over, and narrows her eyes.

Regardless of the crime (murder, theft, bodily disfigurement), few offenders ever suffered punishment in Lincoln. It wasn’t until 1877 that anyone bothered to build a jail of sorts. A hole in the ground was dug and covered with a tarp. This served as the only stockade in all of Lincoln County, an area which encompassed almost half of New Mexico.38

“Walter,” she confirms.

“Mrs. Moss.” I pocket my gloved hands. She eyes me suspiciously. “How are you today?” I ask.

“As fine as could be expected,” she sighs with a pained look that quickly changes to

impatience. “Are you going down?”

“Yes.”

“Well then hurry over, the elevator’s here.”

One local ruffian, convicted of murder and subsequently pardoned, was defended with these words, “You never saw a better fellow than Ham anywhere; he gets mad quick, and shoots quick, but he’s a good shot and never cripples. I really think he is sorry for it afterward when he cools off.”39

We descend slowly. I hover near the elevator door. She wears a perfume that reminds me of my maternal grandmother when I went to visit her at the Saint Antony Home for the Aged. I remember her distinctly emphasizing that the home was named for Saint Antony of Padua and not Saint Antony the Abbot. Antony of Padua is the patron saint of the poor. Antony the Abbot is the patron saint of grave diggers.

Retirement homes and hospitals have always scared me, especially the florid emanations—like a mix of cheap air freshener and roach balm. What I fear most, of course, is what such malodors mask: death and disease, microscopic bacteria squirming aloft among the dust waiting to be breathed into some fertile host. One mere particle would have a field day in my abundant anatomy. My grandmother began as a nurse at Saint Antony and ended up as a patient. The widow Moss reeks of the same deadly redolence. Within the ugly confines of the elevator, I breath slowly through the mouth.

But Billy had worse dangers to fear in Lincoln than short-tempered pistoleers. The Lincoln County War he so eagerly hurried to join was about to explode into one of the bloodiest range wars in the history of the Southwest.40

“Just getting up?” She asked.

“Oh no, got up with the sun, like every morning. Been working at home all day.”

Billy’s Blues

Billy’s Blues