- Home

- Meltzer C. Rips

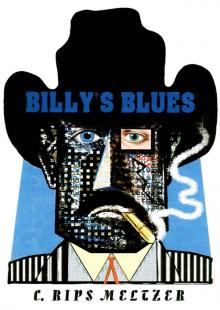

Billy’s Blues Page 4

Billy’s Blues Read online

Page 4

“You look tired. Where are you off to this evening?”

“Now? Well …” I pull out a hand to scratch my head but quickly return it. “I’m taking a course at Metro College. I just signed up.” She eyes the surgical glove.

“Oh yeah, and what course is that?”

“The course? It’s a History course, Mythology of the American Southwest, graduate school. They may let me teach soon.”

“They would.”

“I’m thinking of becoming a professor.”

“You don’t say. I wonder what your parents would have said to that?”

I stand by the door like a dog with a full bladder.

On the road into Lincoln, Billy, now armed with an antiquated .36 caliber Colt Navy, met up with the outlaw Jesse Evans, who had just signed up as a mercenary for the Murphy/Dolan gang. Billy gave his name as William H. Bonney. It was the first known usage of the formal alias he would keep for the rest of his short life. Evans said they could always use another gun, although he doubted the accuracy of Billy’s old percussion pistol.

“You don’t want to test it,” responded Billy.

Jesse explained that they were set on killing one John H. Tunstall an Englishman who had settled in the valley. The outsider had set himself up in direct competition with Murphy and Dolan, also known as ‘The House’ (so-called for the court-like structure built in Lincoln, the largest building in the one-street town, and from which they ruled the region). Billy said he needed to meet a man before killing him. It was bad luck to kill a stranger. Little did the Kid know that the strange Englishman would soon become the father that this poor orphan lad never had.41

“I remember your parents. They were such wonderful people, your father and mother, not like couples today always screaming and yelling and blaming each other for what they don’t have. The co-op could use more people like your parents. It’s a shame what happened. Think how things might have turned out had they not …”

The door opens.

“Aren’t you getting out?”

I step back. “Oh no, you go. Got to go back up. Forgot my books, silly me. But have a good day Mrs. Moss.”

“A good evening, Walter, it’s after six. Some of us get out during the day.”

Even with John Chisum established as the cattle king of the valley, there was still opportunity west of the Pecos. One such opportunist, Major Lawrence G. Murphy, rested out the Civil War at Fort Stanton, a frontier outpost, while feasting his eyes on the small town of Lincoln nine miles east. As the county seat, he envisioned Lincoln as his base for controlling half of New Mexico. As soon as the war ended, he left the military, but used his connections to enter into a lucrative business of selling beef to an army that was now free to turn its attentions toward ridding the Southwest of the pesky Apache. Instead of building his own ranch and going into direct competition with the well-stocked Chisum, Murphy came up with a novel way of acquiring the extensive numbers of cattle needed to fulfill his contracts to the U.S. Army. After the Civil War ended, thousands of ex-soldiers migrated West in search of employment. Well armed, without direction, and often starving, the ex-major recruited them for a new war, one far less dangerous and far more profitable. They already knew how to fight, but Murphy did need to train them for a new skill: cattle rustling.42

Entering the friendly confines of my dark apartment, I peel the gloves off, deposit them in the waste bin, and make my way through the crowded blackness to my room. The answering machine blinks its red beacon. No need to check the message. I know who it is.

Soon Murphy’s military contracts expanded to flour, corn and other staples including lucrative (and dubious) arrangements with the Mescalero Apache Indian Agency. He over-counted Indians, falsified vouchers, and inflated beef weights. He left the Indians with little and the government paying a lot. The local civilians in Lincoln didn’t fare much better. Murphy soon had a monopoly on all goods coming in and out of the area. At “The Store” local farmers and ranchers purchased goods on credit. Backed by “The Law” (and hired guns if need be), Murphy foreclosed on their farms and ranches when they were unable to pay his exorbitant borrowing rates. If that wasn’t enough, he opened “The Bank” and tempted locals to borrow relatively small amounts of money against all their equity. With the younger, but no less ruthless, Jimmy Dolan, Murphy’s protege and partner, “The House” dominated the economics and politics of the region.

This is the world into which one naive but well-intentioned Englishman rode with plans to set up shop, all in the name of healthy competition. His name was John H. Tunstall, and he viewed America as most immigrants of the day: a land of opportunity, where hard work and fair play were rewarded and the corruptions of the old world were left far behind.43

The flashing red light leads me to my bed. I press the cancel button and erase it. I’m suddenly tired.

“Billy lived with me for a while soon after he came to Lincoln County in the fall of 1877. Just before he went to work for Tunstall on the Rio Feliz. No, he didn’t work for me. Just lived with me and my cousin George riding the chuck line. He didn’t have nowhere else to stay just then.

“It was at Dick Brewer’s ranch, just before Murphy’s bank foreclosed on it, that I first met the Kid. Billy had just been turned down for work by Chisum. He had an old pistol in his belt and rode a horse that Pap Jones lent him when he first come into the territory. It was later that Dick introduced Billy to Tunstall. When Tunstall hired Billy he made him a present of a good horse, a nice saddle, and a new gun, a Winchester carbine. My, but the boy was proud. Said it was the first time in his life he ever had anything given him. He said he could not wait to return the old horse to Pap Jones.”

- Frank B. Coe44

I unplug the phone, don the slumber mask, and insert ear plugs. I wrestle with sleep until dawn’s red fingernails reach through the curtains to scratch my back.

Chapter Eight

To date, Henry Michael McCarty, alias “Billy the Kid,” has been the subject of 263 articles and newspaper accounts, 153 books of fiction and nonfiction, 149 copyrighted toy products, 58 moving pictures, 36 government documents (three classified as “Top Secret”), 24 scholarly essays, 14 recorded songs and ballads, six museums, three grave sites, two newsletters, a symphony and a ballet.45

In total darkness, I feel my way to the kitchen gliding a finger along the wall and search for breakfast by the refrigerator light. Supplies are dangerously low. I’m forced to mix Hershey’s Instant Hot Chocolate powder with water and pour it over the last crumbs of Cocoa Puffs cereal. Water is added to apricot jelly for juice. An expedition must be mounted and provisions procured or I risk starvation.

However, more people have come to know of Billy the Kid through the movies than any other medium. It is for this reason that, for better or worse, film has had more to do with the mythology of Billy the Kid than any other factor. In so doing, Billy the Kid on film reveals how America views not only the history of the West, but the very mythology of what it means to be an American.46

Closing the refrigerator door, I’m embraced once again by the night. Hands occupied, I toe my way down the hallway, negotiating the crowded darkness. I pass sideways between overstuffed bookshelves, step over piles of old newspapers, and squeeze through a door that no longer opens all the way.

This is important, for in America, where few can trace their actual history back beyond a few generations, mythology often becomes their only sense of identity, and therefore, far more essential to one’s sense of self than genealogy.47

Taking my mind off breakfast, I review the day’s schedule and scratch off each accomplished task

MON

1) Wake

2) Eat

3) Shower (wash hair?)

4) Dress

5) Clip fingernails

6) Outside

a) mail

b) grocery

Two so far. The next three will be easy. I draw a box around them. I’ll return in triumph after they’re complet

ed.

When history is impossible to trace, mythology takes over.48

INTERIOR: HOUSE LIBRARY—EVENING FADE IN

The room is fitted in late 18th-19th century English decor: an oriental rug, velvet drapes, flocked wallpaper. Furnishings include a Chippendale sofa of inlaid marquetry, two Louis XIV revival armchairs, and a grand piano. Lined neatly with bound volumes, a long walnut bookcase occupies the back wall.

Two men enter through an archway framed with laced portieres. One man is dressed like an English gentleman smoking a pipe. The other is dressed like an American western outlaw wearing a holster with a pistol.

BILLY THE KID

What kind of room is this?

TUNSTALL

This is the library, Mr. Bonney.

Billy looks about in childlike wonder as Tunstall lights his pipe.

BILLY THE KID

You don’t see much of rooms like this around these parts. Look at all them books. Have you read all that?

Tunstall smiles and lowers his pipe.

TUNSTALL

Many, but not all. Some books are meant for other purposes than reading cover to cover. This set of volumes, for example, is an encyclopedia. You use it for reference … to look up things.

BILLY THE KID

Like what?

TUNSTALL

For example, earlier today you inquired about my accent and why I carry no sidearms.

BILLY THE KID

Yeah, you talk like a King of Diamonds, but act like the King of Clubs.

TUNSTALL

I come from England. Our ways are different over there. You could read about England in an encyclopedia.

BILLY THE KID

I don’t take to far away places. Seems a waste of time thinking about where I ain’t. I like to think about where I am.

TUNSTALL

What about your forefathers, do you not care about the country from whence they came?

BILLY THE KID

My mother said we holler from a place called Ireland, but I never gave it much thought.

TUNSTALL

Are you not interested in learning about your past?

BILLY THE KID

The past don’t concern, me. I only care about today—right here, right now.

TUNSTALL

There are those who might consider that a practical view.

Billy rests his hand atop his pistol.

BILLY THE KID

Oh I’m practical all right.

Tunstall casually lights his pipe.

TUNSTALL

Your reputation with a pistol precedes you, Mr. Bonney. Please forgive my forwardness, but may I ask if you also possess the ability to read?

BILLY THE KID

I had me some schooling.

TUNSTALL

Have you ever read the Bible?

BILLY THE KID

Ma read parts to me.

TUNSTALL

Have you read it since then?

BILLY THE KID

Never owned a copy.

TUNSTALL

Do you own any books, William?

BILLY THE KID

Books weigh a saddle bag down.

Tunstall reaches to the bookcase, pulls out a Bible and hands it to Billy.

TUNSTALL

Accept this copy as a gift.

Holding the Bible like it was fine china, Billy looks down at the book, hesitates, and looks back up at Tunstall.

BILLY THE KID

I … I can’t carry something like this around. Why … it weighs near as much as my six-shooter and I’m not about to lay that down.

TUNSTALL

What if you had a place to lay your Bible, William, or for that matter, anything else that weighed you down?

BILLY THE KID

What do you mean by that?

TUNSTALL

I mean that I am offering you a job, my dear fellow. You told me before that you found Murphy’s methods distasteful. You also said that you would never shoot a man in the back or one that was unarmed, but how long will you be able to say that if you ride for Murphy? Hang your spurs here and you can earn an honest living. Is that not what you really want? Is that not what your dear mother would want?

BILLY THE KID

My dear mother’s dead, Mr. Tunstall, and I’m wanted, dead or alive, for shooting the man that insulted her.

TUNSTALL

You said before that you are not concerned with the past. Well, neither am I. I care about the kind of man you are today, Mr. Bonney, the man standing before me, right here, right now. That’s the man I want working for me.

BILLY THE KID

But I’ve never punched cows Mr. Tunstall. I don’t even know if it’s in me.

TUNSTALL

I believe whatever William Bonney decides to do, will be done.

Billy looks back down at the Bible in his hands.

TUNSTALL

I’m offering you a way to start over again, man, a way to wipe the slate clean, to begin anew. With the past behind you, your future is an open book.

BILLY THE KID

I just don’t know Mr. Tunstall.

TUNSTALL

Don’t make up your mind right away, my boy, just promise me that you will give it some thought. In the mean time, you are welcome to stay the night and leave in the morning. Darkness has settled upon us and I fear a storm is brewing.

Tunstall smiles a moment before resuming.

TUNSTALL

It would be a shame for that Bible to get wet.

FADE OUT49

Referring back to the list, I update my progress.

3) Shower (wash hair?)

4) Dross

5) Clip fingernails

Each achievement, each bold scratch of pen, marks my daily progress. Already a day well spent, now to forge ahead.

6) Outside

a) mail

b) grocery

Grocery … I should expand upon this. If I’m to go out there, I should be prepared to face the wilds in as civilized a manner as possible. Organization is the weapon of choice. The list needs detail.

b) grocery

- Hershey chocolate bars

- Marshmallow Fluff

- Skippy Honey Nut Peanut Butter

- Reddi-Wip Instant Whipped Cream

- Mini-Oreo Cookies & Cocoa Puffs

- Milk

- Rolaids

I hear what sounds like a puppy yelping, a bark mixed with more fear than intimidation. I didn’t know my neighbors owned a dog. Not Mrs. Moss of course. Nothing could live with her I fear, not even a dog. These two are a childless couple. The man has a voice that goes through walls.

“Shut up, you mangy mutt!”

Now they’ve got something new to fight about.

“Good lord!” His voice rises. “Come over here. Look at this. I thought you said you walked the dog?”

Such interruptions are terribly distracting. How can anyone get any work done? Her voice is so low, I can’t make out her response. I grab a glass from the kitchen and cup it against the wall, my ear pressed to the bottom.

“Did I want the dog?” He asks accusingly.

“I thought it was your idea,” she answers meekly. I can barely make her out.

“My idea? So now it’s my idea. You always say it’s my idea when anything goes wrong.”

“No I don’t.”

“Are you calling me a liar?”

“I didn’t call you a liar. I just said it wasn’t my …”

“Now you want to change the subject. We’re talking about the dog here, about the mess your dog made on that brand new rug, the rug that was bought with my money, the money I sweat my balls off for and you throw away on stupid pets.”

“But it was …”

“Don’t but me,” his voice crescendos. “Who’s responsible for the dog?”

“I am, but …”

Now shouting, “Answer me—don’t but me!” There’s a pause before he speaks again. This time his voi

ce is ominously low.

“Now, who’s responsible for the dog?”

“I am.”

“So who’s responsible for that shit on the rug?”

“I am.”

“Then why did you let it happen?”

“But …”

“Don’t but me!” I hear the hollow sound of a fist hitting the side of a face. The puppy resumes its frightened barking from the other room. Involuntarily, I spring back losing contact with the glass. I carefully place it upon the wall again.

“Look what you made me do.”

I make out muffled sobs.

“When I let you get the damn dog, you said you’d take care of it. Now we’ve got a little eat, piss, shed and shit machine on our hands. You say you want kids? You can’t even take care of a dog. Are you listening to me?!”

“Yes, yes,” she says between sobs.

“LOOK AT ME WHEN I’M TALKING TO YOU!”

“I’m sorry, please, I’m looking, I’m looking.”

“Train the fucking dog or you get more of this!”

I picture his hand raised again. She cringes and covers up.

In conclusion, the actual facts concerning Billy the Kid, or anyone’s life for that matter, has no historical relevance or meaning, per se. One’s actual life remains private, unexposed, a mystery. Its meaning, value, or actuality exists only in what people believe to be true. The public mind determines history and, subsequently, its relevance or meaning from that context. This historical consensus then, reveals not only how we view ourselves, but how we wish to be viewed by others. Billy the Kid, as a factual entity, exists only in the present public perception (continually in flux) and therefore functions as just another barometer of the American mind.50

A door slams. In the distance, frightened barking resumes. Then I hear the man’s voice merge with the puppy’s in the echo of the other room, “Damn mutt!” There’s a thud like a foot kicking fur-lined ribs. The puppy whines in short frantic yelps.

My phone rings sending a lightning bolt through my heart. The glass drops from my hands and crashes to the floor. The answering machine clicks in. I desperately clasp my hands to my ears. I don’t want to hear anything anymore.

CUT TO

EXTERIOR: PORCH—EVENING

Tunstall walks out of his house on to the porch. Lighting a pipe, he looks into the distance deep in thought. Unseen by Tunstall, Billy walks out of the darkness and stands at the bottom of the stairway.

Billy’s Blues

Billy’s Blues