- Home

- Meltzer C. Rips

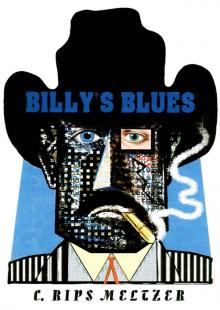

Billy’s Blues Page 2

Billy’s Blues Read online

Page 2

“When Henry Antrim came to Fort Thomas and asked for work, he said he was seventeen, though he didn’t look to be a day past fourteen. Didn’t know nothin’ about horses, nothin’ about cattle and could handle neither rope nor gun. We had trouble finding things for the boy to do, because he weren’t no cowboy. Had to let him go though we gave’m money enough for a new set of clothes. Heard later he strayed over to Camp Grant.

“Called him ‘kid,’ because he was so small: no taller than a mule, no heavier than a sack of flour. When they told me later that he was the Billy the Kid, the same one who fought in the Lincoln County War, I said, well doesn’t that beat all. Must’ve grown some.”8

- W.J. ‘Sorghum’ Smith

Yes, he had wandered into the notorious Apache triangle as a boy, but came out two years later man enough to make his home among soldiers whose only relief from harsh army life was drinking, gambling, fighting and whoring. He also came out man enough to commit his first official murder deflating Windy Cahill, the camp blacksmith and bully, with a bullet in the stomach on the night of August 17, 1877.

I, Frank P. Cahill, being convinced that I am about to die, do make the following as my final statement: I was born in the county and town of Galway, Ireland. Yesterday, August 17th, 1877, I had some trouble with Henry Antrem, otherwise know as Kid, during which he shot me. I had called him a pimp, and he called me a son of a bitch, we then took hold of each other. I did not hit him, I think – saw him go for the pistol, and tried to get hold of it, but could not and he shot me in the belly. I have a sister named Margaret Flannigan living in East Cambridge, Mass. and another named Kate Conden, living in San Francisco.9

According to witnesses, Cahill had wrestled young Henry to the ground and began pummeling him with his thick fists. Half his weight, the boy reached for the blacksmith’s own gun. He pulled the hammer back and squeezed the trigger while Cahill was in mid-punch. It was the first time the boy had ever fired a pistol.

Declared an “unjustifiable killing” by a grand jury, Henry was arrested, hand-cuffed, and thrown into the fort stockade which was filled with soldiers—traitors, deserters, and murderers of which he could now include himself, many of whom faced the firing squad. Civilians got the rope.

Old enough to kill,

Old enough to hang. 10

A few nights later, as Captain G.C. Smith entertained guests in his quarters, shots rang out in the dark. It caused little excitement, but according to army procedure, the young Lieutenant Cheever, officer of the day, was sent out to investigate. He returned to inform Captain Smith that the sentries had fired upon one Henry Antrim, commonly referred to as ‘the kid,’ who had escaped into Apache country on ‘Cashaw,’ civilian John Murphy’s racing pony. Awaiting orders, Lieutenant Cheever was surprised when the Captain simply offered him a fresh drink and told him to rejoin the party.

A week later a trader rode into camp with Cashaw. He said a runaway boy had asked him to return the pony to its rightful owner. Henry was on the run again, without horse or gun, but with outstanding warrants in both Arizona and New Mexico. An unwanted boy, yet a wanted man, Henry was now alone in the wilderness once again and unwelcome in both mining towns and forts. Forced into the life of a desperado there was only one place he knew of where outlaws were welcome. That was in the valley of the Pecos River, where men fought over cattle, land and women, and no one much cared about your past. He had already traveled west to escape Silver City, now he’d have to travel back east through Silver City to get to the Pecos Valley. At least he knew people around Silver City. He planned to rest before traveling through the desert of Jornada Del Muerto (Journey of Death, and later, the White Sands Missile Range). He had never traveled through a desert before, but he figured that there would be fewer Indians there. At the age of seventeen, the kid still had a lot to learn about the Apache.

Olinger ran out of the saloon and crossed the street as old man Geiss, the cook, crossed the yard of the courthouse and appeared at the front gate. “Olinger,” he said stopping the deputy in his tracks, “the Kid has killed Bell.” At the same instant the Kid’s voice was heard above: “Hello, Bob,” said he.

“Yes,” Olinger coolly replied to Geiss as he stared down the barrels of his own shotgun, “and he’s killed me too.”11

My phone rings. The answering machine kicks in.

“Hello … Hello … Hello …?”

Helios rises. His bright eyes reach out over the rows of dark cavernous buildings that make up the Bronx. I could try to sleep or go to the lobby, fetch the mail left uncollected for days, maybe even go out for milk. It’s been a long time since I had fresh milk. I should make up a list and do a real shop. Yet something compels me to turn out the lights and sit here as daylight slowly fills the room. Sunstreams highlight the dust swirling through each beam like newspapers in the wind. Called Mormon rain, it accumulates into devil’s snow on the floor. Drifts form and fill corners, hide beneath the bed and behind the dresser, cling to fallen socks and misplaced paper clips. How can there be so much movement in the air while I sit so still? From where does such charged energy come? What gives the air such life?

I draw the curtains closed, don my slumber mask, insert earplugs, and do battle with sleep.

Chapter Three

“My name is Anthony Conner, but people call me Tony. I grew up in Silver City, New Mexico with Billy, or Henry as we knew him. More’n two years after Henry busted out of the Silver City Jail, he rode into my brother’s ranch … my brother’s name is Richard Knight … same mother … older. Do you want to hear about me, or what I know about Billy the Kid?

“As I was saying, Henry rode into the ranch a few years after he escaped up the chimney of … The ranch? Our ranch is located in the Little Burro Mountains forty miles southwest of Silver City. Now are you going to keep interrupting me or let me tell my story?”12

The dream continues …

Again, my bodiless soul hovers above the campfire. Below, the strange manchild stands before my sleeping figure, lying there so still and vulnerable. As his darkened figure shadows over my old body, the relief of being released from such a weighty anchor is somewhat diminished by a sudden sympathy for the lifeless hulk below and an inexplicable desire to return to its painful yet defining restraints.

The campfire flames flicker behind his sinister silhouette framed by a large sombrero. The front of his poncho, pulled over his left shoulder, reveals his rifle, barrel low. From above, the sombrero hides his features, but then, as if on cue, my perspective changes. I’m lying on the ground. I feel my body again: my soul nestled in warm flesh, skin itchy beneath a rough wool blanket, face flushed by the flickering fire, and both eyes staring up into the barrel of a Winchester carbine.

“He told my brother what he’d done. Remained about two weeks, but fearing the officers from Arizona might show up any time, he left and never returned.”13

I feel numb. I’m awake yet immobile as if my body still sleeps. I strain to move, but an invisible rope seems to tighten the more I struggle until it becomes difficult to breathe. I stop struggling and slowly regain my breath.

“Henry was kind of quiet when we was schoolboys, but he took a liking to our teacher, Miss Richards. Henry used to help her around the schoolhouse … oh, chores and stuff. We used to tease him that he was the teacher’s pet. Henry didn’t like that. After his mama died, he came over to live with us. He worked in my brother’s butcher shop in town and I know for a fact that he never stole anything. We left Henry there alone all the time and never noticed anything missing. We couldn’t say that about others that had worked there.

“He never swore or acted bad like other kids. When a few of us boys got together and started a minstrel troupe, Billy was head man in the show. Got a standing ovation over at Morrill’s Opera House.”14

Looking up to the silhouette before me, I try to distinguish his features more distinctly. The face beneath the hat is boyish, an obvious stranger to the blade. Dirty blond hair frames bright blue

eyes. The most outstanding feature, however, is a pair of bucked teeth, slightly crooked. Otherwise, his eyes betray more charm than gruff as if at any moment he’d break out into a smile that would make one proud to call him a friend.

“A real good singer and dancer, Henry was, but he was smart too. Henry got to be a reader. He would scarce have the dishes washed until he’d be off somewhere reading a book … Dime novels and such, the Police Gazette. Oh yeah, there was this series about a team of lawmen, vigilantes, who rode the West in search of bad men. What did they call themselves? I remember, ‘The Regulators.’ Henry loved reading about The Regulators. He wanted to start a gang and call it that, but nobody wanted to join a gang of do-gooders. We all wanted to be badmen.”15

But with the rifle slung low, he isn’t smiling now…

“When Sarah told him he could pick any horse … Sarah Ann Knight, my brother’s wife … any horse he wanted out of the corral, he picked the scrubbiest of the lot. Before he left, he told me he was thinking about drifting over to Lincoln County and joining the war. When my brother Richie asked him what side he was going to join, Henry said he did not know.”16

Chapter Four

“Hello … Hello … Hello …?”

The daily news records time in such a way that gives detail to man’s existence, and thus, provides much of the material from which future generations will determine our historic definition. Without the news, how could one ascertain one’s own place in time? Therefore, my evening always begins with the newspaper. News stimulates the waking mind, puts one into the mix so to speak. Although my day begins with night, reading the paper is one of the few rituals I share with the waking world. Going outside directly afterwards, however, is another matter entirely.

DRUNK DRIVER DRAGS

TODDLER 20 BLOCKS

License Suspended 64 Times

The Igbo tribe of West Africa, most notably southern Nigeria, believed that the first person with whom you exchange greetings on any given day is the most important. If they are friendly and trustworthy, your day will go well. If they are hostile or indifferent, your day will go badly. Subsequently, it is especially important to ignore everyone until you can exchange greetings with the right person. I believe this to be a wise policy and have found it substantiated many times.

FAMILY OF FIVE

MUGGED AND SHOT ON SUBWAY

Trainload of Commuters Watch Silently

Unfortunately, the times we live in are especially foul and disagreeable. The newspaper awaits me each evening, perched recklessly behind the front door, waiting to fall into my foyer and release the ugly world into my safe haven. Although I faithfully read it, front to back, even if it takes all night, I find within it enough evil (nation upon nation, government upon citizen, parent upon child) to last indefinitely.

SERBIANS KILL MUSLIMS

MUSLIMS KILL CROATS

CROATS KILL SERBS

Just Another Day in Bosnia

Modern society has returned man to the primeval forest. Meaningless jobs reduce us to operating with our most base instincts. We’re like leopards hunting in concrete jungles overgrown with greed: survival of the fittest with money replacing food. Families separate as soon as possible. Parents can’t wait for their kids to grow up, get out and support themselves. Upon growing up, children can’t wait to commit their parents to nursing homes.

SNIPER KILLS MOM

Modern leadership has reduced itself to governing populations by statistics. The individual feels like a number on a list or a worker ant in an overgrown anthill. Neighborhoods have disintegrated into high-security skyscrapers where apartment dwellers know little of the people next door, or into ghettos where parents keep children indoors for fear of random gunfire.

Such isolation breeds anonymity, and anonymity breeds detachment from all obligation or decency. Words such as “good” and “bad” no longer have a clear definition beyond whether or not one gets caught. How can anyone get caught if everyone is too cynical, hardened, or plain scared to bother paying attention to anything but the most outrageous acts? Print a story about a 5 year old girl tortured to death by her parents and they line up for blocks to view the corpse, tears washing away the guilt of their own crimes against humanity. However, if they hear yelling, smacking, and crying next door, they bury their heads deeper into the pillow, roll over, and try to get some sleep.

NOTEBOOK, PAPER, PEN, AND A

9 MILLIMETER SEMI-AUTOMATIC

Junior Is Ready For Another Day At School

Anonymity breeds lawlessness. No one understands this better than children. Leave a group of children unsupervised in a room, come back in a few hours, and you’ll witness a pecking order independent of morality if not complete disorder. Children need parental supervision. Grown-ups either need a strong community consensus of those they know and respect or, if all else fails, the fear of God. Now that man has isolated himself from his fellows, and God for all practical purposes is dead, who will check man’s natural inclination towards selfishness in the name of survival of the fittest? In the ensuing chaos, man’s Darwinian instinct for self preservation will kick in. He’ll justify all kinds of law and order legislation based on “an eye for an eye” mentality of revenge.

Bring back the death penalty, the more painful the better.

It merely reinforces that might is right.

Why waste time, money and energy on rehabilitation,

when corporal punishment is quicker, cheaper and easier?

For every dollar we take away from education, ten is spent on institutionalization. For every new prison we build, another school deteriorates into a holding cell. The kid you toss out on to the street today without skills or self-esteem is the punk that will mug you tomorrow. It’s no wonder that youth crime is rising and will continue to rise in spite of all the feeble attempts by politicians, bureaucrats, and the other institutional icons of modern man to stem the tide. The young intuitively develop the very skills they need to survive. What models of behavior are left that offer them a practical alternative?

The Igbo had a simple saying for this, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

IS THE KING OF POP

A QUEEN OF PERVERSION?

Boy’s Family Charges Singer With Molestation

As the mind of man gets simple, society deteriorates and everyone becomes a potential threat. We’ve become a nation of falsehoods, a society of strangers, people hiding their true feelings in fear that it can and will be used against them. The modern forest is more sophisticated, the pecking order more complex, and the armaments more deadly. Without guile, a simple man like myself is unarmed against such weaponry and unprotected from the evils slyly hidden behind the smiling masks worn by others.

WACO WACKOS BURN

Botched Raid on Branch

Davidians Fueled by Fate

Consequently, during my first foray of the day, I’m unable to acknowledge the neighbors. In a co-op, this is not always the best policy. My monthly maintenance bill is automatically paid from my trust account each month. My apartment was paid for in full after the family tragedy. Regardless, the co-op board has been trying to rid the building of me since I came of age and has engaged in an endless running battle with my lawyers (praise the Gods I inherited them as well). I’m regarded as an unsuitable tenant, me, who humbly keeps to himself. Where they got this idea, I do not know, but I can hardly exchange greetings with such people. It would be opening the door to their evil without defense.

TEENS TOSS OBJECTS

OFF PARKWAY OVERPASS

Bowling Ball Bashes Baby’s Brains 17

Although I’ve lived here throughout childhood, I know few by name. How can I take a chance greeting strangers? Any Igbo worth his salt would have eagerly concurred. It was strongly recommended that if one is forced to exchange pleasantries with a hostile presence, one must return home at once and not go out until the next sunrise or risk imminent danger.

However, I can avoid the hostiles that s

urround me if I make it to the lobby, a bastion of safety. There, doormen patrol around the clock. Doormen are excellent people with whom to exchange first greetings. They always smile and say hello in an unthreatening and sincere manner.

Driven south, young Henry made his way into Mesilla, just 25 miles north of the border. It was the closest he’d ever been to Mexico, but he might as well have been south of the border for he had never seen so many Mexicans before in all his life. The men wore wide-brimmed hats and loose clothing that seemed very practical to a boy who had just ridden almost 150 miles through some of the roughest country in the southwest. The women made an even deeper impression on the young man. Long black hair, rich auburn skin, and deep dark eyes with an intriguing mixture of sadness and mystery beckoning him, as if the man who possessed the right key to their hearts could unlock the secret to life.

It was here that young Henry started picking up his first phrases of Spanish, a language he took to quite naturally.18

I’ve even learned salutations in the Spanish language as a sign of mutual respect. The doormen respond benevolently, tolerating questions on the subtle differences between hasta luego and hasta la vista with infinite patience.

It was also in Mesilla that Henry met another Irish youth his age, Tom O’Keefe, and together they decided to set off for the cattle-rich Pecos Valley in search of work. When asked for his name, Henry answered, “William Antrim, but you can call me Billy.”19

Such exchanges, always friendly, set a favorable tone, forming a protective armor of positively-charged ions shielding me from the ugly, unsterile world.

Tom had good news for Billy. If he would meet him just before the sun rose on the outskirts of town where the road forks off to the old Spanish graveyard, Tom would show up later with a pair of horses, one for Billy to ride. Billy was not about to look a gift horse in the mouth and readily accepted. He’d been walking so long he’d taken to plugging the holes in his shoes with newspaper.20

Billy’s Blues

Billy’s Blues