- Home

- Meltzer C. Rips

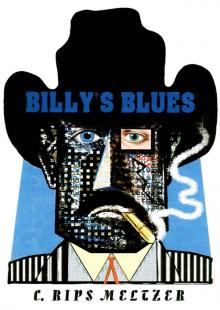

Billy’s Blues Page 6

Billy’s Blues Read online

Page 6

She short-steps into the elevator cab reeling in the puppy. The puppy glues itself so tightly around her ankles that she stumbles slightly as she hits the lobby button. Wedging herself into the far corner, the puppy hides behind her bony, spinach-veined ankles.

Feeling like Thrasymachus gazing upon the eyes of the dead, I can’t resist looking at the woman across from me, her face hidden beneath the brim of her whimsy. She wears stiletto high-heeled shoes which seem highly inappropriate for dog walking. Tight black leotards accentuate mannikin thin legs. She wears an orange paisley vest and a loose white shirt buttoned up to the collar (praise the Gods!) but fails to hide a pair of hands and wrists so bony and fragile the skin seems more like webbing. The momentary glimpse I had of her skullish face betrayed features which once may have been attractive. I catch a glimpse of circular earrings which appear larger than her shrunken ears.

With her gaunt body, she appears to suffer from anorexia, a disease I fail to understand. I’m reminded of a childhood memory, a grainy black and white film clip I once saw as a young boy on the liberation of Aushwitz during World War II. As bulldozers shoveled mounds of the unclothed dead into large graves, the body of a women, teetering on the edge of the ditch, was finally nudged over by a blackened boot. As the camera followed her tumbling sideways over bodies, her dark hair hid her face, her arms flailed like loose string, her lifeless breasts sagged sideways, her pubic hair, black against the palest of white skin. I was filled with dread and experienced a fear so primal, completely beyond explanation, the kind you never outgrow. Later, I experienced nightmares of being dumped over the precipice by a bulldozer with the other bodies.

As the elevator descends, lifting my bodyweight slightly off my feet, I feel a strange chill through my back and shoulders, and I’m transported back in time to that childhood vision, that all-encompassing moment of which only children seem susceptible. Falling among the corpses again, I’m tangled in the dead woman’s arms, her hair blinding me, tumbling over the other bodies to the muddy bottom until she lands on top of me and I’m buried alive suffocating in her rotting thatch for all eternity.

The elevator stops. The door opens. All three of us stand immobile.

Sensing some sort of pursuit, the small flock of turkeys scrambled out of the gully with Brewer and Widenmann hot on their tails. At this point, with the fowl fenced In and confused, Brewer and Widenmann could have jumped off their horses and bagged their quarry by hand, but a real cowboy doesn’t dismount unless absolutely necessary. Instead, each tried to grab the birds by the neck while mounted. This made for a great challenge and much joviality. The turkeys, not amused at this play, flayed their wings stirring up the dust and gobbled loudly drowning out the men’s laughter as the hunters leaned over and grasped handfuls of air. In the confusion, the lead bird found a way out sending them all further down the gully. Brewer and Widenmann could have then taken out their rifles and easily plugged a few, but that did not seem sporting, and although neither of them conversed on the Issue, they were in mutual agreement that the way to proceed was to follow the turkeys’ lead and continue the pursuit.

At the bottom, the turkeys were again trapped. Brewer reached down and finally grabbed one by the neck. In his glee, he raised the captured fowl above his head and shouted to Widenmann, “Hey Bob, looky here, don’t this one paint a nice picture.”

That’s when they heard the first shots.58

They exit the elevator and find unsure footing on the slippery lobby floor. She wobbles gingerly on high heels. The puppy strains against a short leash scurrying in place and flopping on its side. Since we carefully avoided salutations, I feel no Igbo would judge me wrong in proceeding. Still, before following, I check the hallway. At the end, I see the doorman assisting an older woman with her two-wheeled shopping cart up the stairs. She’s short, wide, and wearing a thick coat … it’s Mrs. Moss and she’s heading this way! Before they see me, I take cover.

I hear Mrs. Moss’s voice cackle, “Hold the elevator, please.”

I quickly press the close door button, breaking a fingernail which sticks through my glove like a broken bone through skin.

“Hold the elevator. Can’t you hear me?”

Protecting my wounded finger, I press myself tightly against the paneling.

“Hold the door! Who’s in there?”

Please, please, close the door.

“I’m almost there, can’t you hold the door just one second?”

At this point, dear reader, you may want to pause before reading further. The following account of the Incident between Murphy’s blood-thirsty “posse” and the kind-hearted Tunstall may not be suitable for the tender ears of young innocents or women In a family way. Of the countless dastardly deeds recorded during that short epoch of history so aptly named the Wild West, the following ranks as the most dastardly and desperate of them all.

Buck Morton was the first to get within range. As the trusting Englishman raised his right hand in salutation, clearly unarmed, Morton raised his rifle and fired, shooting the unsuspecting gentleman through his tender heart. With one hand grasping his noble breast, the other raised to the heavens, the good squire fell off his modest chariot and onto the ground. As he wallowed In the dust gasping for fresh air, the evil Jesse Evans pulled out his revolver and shot the helpless soul In the back of the head. To make sure the deadly deed was done, Morton dismounted and crushed the dying man’s head with the butt of his carbine as Segovia “the Indian” picked up stones and pelted the twitching torso. Baker, not to be outdone, finished the devil’s work with two barrels of buckshot nearly cutting the courtly corpse In two. Gleefully, Dolan witnessed the dirty work of his bestial pawns, not missing one tasty detail. Later, he’d relate the morbid merriment to Murphy over drinks and derisive laughter.

The fallen prince’s horse, confused at his master’s sudden Immobility, licked a bloody ear. The outlaw Jesse Evans, untouched by this tender display of loyalty, re-cocked his pistol and gleefully shot the poor beast between the eyes, laughing with a chill that the devil himself found distasteful. Their blood-lust boiled, the blue jean clad gargoyles began mutilating the lifeless body of Tunstall with jagged rocks and an axe from the wagon in such a ghastly and unspeakable fashion that I ask to be forgiven by historians and antiquarians alike for not objectively detailing such deprivations, and failing in my duties as a writer to precisely record history. For those who desire such facts, I pray you find satisfaction elsewhere. Suffice it to say that in capping off their twisted sport, one Frank Baker joined in to help Hill and Morton lay the poor horse besides its kingly master. Using Tunstall’s coat and hat as pillows, they fashioned the pair as if sleeping side by side while facing heaven. Their laughter over this final display of divine mockery, echoed ominously over the hills.

Pinned down by Murphy’s forces at a distant hillside, Billy blasted away at the enemy with his six-shooter, John Middleton cowering at his feet. As bullets grazed his youthful waves of hair, hot tears streamed down his rose-bloomed cheeks.

Miles away, the real Indian, Fred Waite, turned back from his scouting duties to join the others when he spied a golden eagle flying above him. Such birds were considered by the Choctaw to be sacred. The heavens sent messages of portent through the actions of our flying cousins. One had to watch and listen in order to interpret their actions.

As the great bird’s shadow passed overhead, It suddenly swung down In the direction of where Waite had left his compadres. It swept Its large wingspan inches above the ground, opened its razor sharp talons, and snatched a prairie dog puppy for dinner.

Waite spurred his horse knowing he was too late.59

As I enter the apartment, the phone is ringing. I throw my hands over both ears and hum loudly until it passes.

“Little Coyote,” Waite whispered into the grieving Kid’s ear, “I think it’s time to start that ranch on the Penasco like we planned.”60

I tend to my wounded finger and revise tomorrow’s schedule.

&n

bsp; Chapter Ten

According to most historians, western frontier aficionados and other amateurs whose books crowd library shelves and discount bookstores, John H. Tunstall’s death signifies the official beginning of the Lincoln County War. However, this supposition can only be true if the definition of war is written in blood alone. Otherwise, a more modern sensibility marks this violent action as the point where the escalating conflict made a transition from a “cold” war to a “hot” one. And hot it undoubtedly became. Of all the range wars waged during the 30 year period of post-Civil War southwestern U.S. settlement (commonly known as the “Wild West”), few were more steeped in blood than the contest for Lincoln County. Even the notorious Johnson County War paled in comparison.61

Darkness. Silence. Warmth.

Earplugs inserted, I lie in bed buried beneath the covers. I lie completely still, breathe my own dioxidous air, listen to my heart beat. The thickness of night blankets my soft cocoon. Out there, I imagine the world asleep—lights out but for street lamps, the occasional car, or some unfortunate soul shaken out of slumber by a bursting bladder, unhappily forced to enter the harsh light in a cold search for relief.

ACT TWO

The lights dim, but before the curtain rises an old English song “The Three Ravens” fades in on guitar and violin. Played mournfully like a funeral dirge, the singer sings with much expression.

Down the hill in yonder green field,

(Down a down, hey down, hey down)

There lies a knight slain under his shield.

(With a down, down, derry, derry, down)

His hounds they lie down at his feet,

(Down a down, hey down, hey down)

So well they do their master’s keep.

(With a down, down, derry, derry, down)

The curtain rises.62

But me, here, alone in the belly of my bed, breathing slower and slower, heart releasing its grip and growing lighter, beating less and less until a single tap nudges gentle waves through my body like a babbling brook in the garden of serenity. Each pulse, like a pebble tossed in the center of a pond, forms ripples of relaxation flowing happily into unburdened limbs. I feel my soul pass through these fingertips as the ruffled sound of water ebbs through mossy rocks, down hillsides into burgeoning pools, over embankments and into rivers, and finally returning to the all-embracing mother, the sea, embracing her children while singing sweetly a tidal song of peace and harmony with the moon and stars.

Floating away on the curves of her canzonet, her lullaby of space and time, her Novus Magnificat into the fifth dimension, leaves me both empty and filled with everything and nothing, a complete sense of personhood yet fully a part of the greater whole. It tells me, yes, I am the center of the universe. All consciousness begins here, all perception comes from this source, this pocket of warmth, this little perfect circle of being, of form and content, matter and metaphysics, skin and spirit—and I no longer feel alone, as if some presence allows this source of safety, this pouch of protection to embrace me in its all-encompassing hand and fend off the icy fingers that seek to rip me out into the frozen cold and toss me before the ice-cube dagger thrusts of brute anonymity and question.

SCENE: McSween sitting room.

Stage left, Mr. McSween is sitting at the piano, elbows on the keyboard, head in his hands. Mrs. McSween is standing behind him, hands on his shoulders. The rest of Tunstall’s men (Brewer, Widenmann, Middleton, Waite, McCloskey, and George Washington, the ex-slave, are scattered around the room, sitting in chairs and leaning against the wall.

Stage right, we see Billy the Kid sitting at a table deeply absorbed in cleaning his guns. As the scene progresses he will be seen winnowing his Winchester, inside and out, first oiling it, then polishing the barrel and waxing the wood before switching to his pistol.

MIDDLETON (leaning against a wall)

Well, what’ll we do now? (looks towards Brewer and adds accusingly) You got any ideas, Dick?

BREWER (sitting)

You act as though it’s my fault!

MIDDLETON

You didn’t hesitate giving out orders before we left the ranch. What was that I recall you saying: (switches to a mocking, high-pitched voice) “At the first sign of trouble, take to the hills boys.” We didn’t think that meant leaving Mr. Tunstall behind, did we boys?

BREWER (standing up)

Are you calling me yella?

MIDDLETON (straightening up)

If the boot fits …

Brewer leaps out of his chair toward Middleton …63

But here, safe in my warm darkness, I’m fully condensed into pure being, yet, paradoxically, I feel more a part of the great expanse of existence. It’s as if the whole universe had shrunken itself into my inner darkness, been sucked into my being—yet, at the same time, this same darkness, this being swallowed into nothingness, expands back into the universe like a black hole in reverse. Each extreme—the smallest of small, the largest of large—equals the same infinity, each opposite—the ultimate peace, separate, yet so much a part of everything that such words as fear, anger, and pain lose all meaning, as if such trivial concepts are beneath the comprehension of floating souls. Then I feel myself slipping even further away, into a consciousness beyond sleep, beyond weightlessness, beyond …

The phone rings, rudely shaking me from my reveries.

Billy, rifle in hand, leaps between the two men.

THE KID

Please! There’s a lady in the room.

Mrs. McSween nods back in thanks and then goes back to consoling her husband. Brewer and Middleton regretfully return to their previous positions. The Kid sits, puts his rifle down, and now begins cleaning his revolver with the same methodical care.

WIDENMANN (with German accent)

Since eet ees I zat vas herr Tunstall’s closess friend, eet ees I zat should take over.

BREWER

I’ve never taken orders from you, and I’m not about to.

WIDENMANN

Zen maybe eet ees about time zat you take orders instead of give zem.

BREWER (rising again, fists clenched)

Why you dirty little …

THE KID

Watch your mouth, Dick!

WAITE

Brewer, Widenmann, everyone—there is only one here who deserves to be chief.

All eyes turn expectantly to the Indian, except McSween, who has not raised his head from his hands. Waite reaches into his pocket and takes out Tunstall’s old pipe. With two hands he carries it over to McSween. All eyes now settle on the Scotchman who hasn’t moved. Then, like a daydreaming student who realizes that the teacher has asked him a question, he raises his head and looks around the room until he notices the Indian before him and then the pipe. Recognizing the pipe, he carefully takes it. He looks back around the room and then to his wife. She nods in confirmation. Grasping the pipe, he stands and straightens his jacket.

McSWEEN (looking around the room)

When I was asked by Tunstall to become a partner, he said to me, “Alex, if you join my cause I want you to promise me that no matter what outrage Murphy and Dolan commit, you will not be a party to any kind of retribution that goes outside the laws of God and man.”

I will tell you now, as God and man is my witness, I intend to keep that promise to the grave. If I take over, each one of you must also make this solemn pledge.

McSween looks around the room imploringly. The men look at each other, all except The Kid who has preened his pistol and now loads it with bullets. McCloskey then steps forward with an exaggerated air.

McCLOSKEY

I pledge myself if it means anything Mr. McSween, sir.

McSWEEN (grabbing McCloskey’s hand) Thanks my son. (McCloskey looks down at his hand, back up at McSween, and smiles awkwardly)

THE KID

That’s easy for you to say McCloskey, you weren’t there, were you?

McCLOSKEY

(gladly pulling his hand away)

If I

had, I wouldn’t have just sat and watched.

THE KID (standing with revolver)

Why you … (spins the pistol into his holster) I do believe it’s time to step outside.

McCLOSKEY (raising his hands in surrender and stepping back)

Now Billy, I didn’t mean anything …

McSWEEN

(stepping in front of McCloskey)

That’s enough! This is exactly what I mean. If we resort to violence, we descend to the level of our enemies. Fighting amongst ourselves is exactly the kind of behavior Murphy and Dolan figured after Tunstall’s death. It’s exactly what their men would have done. We must be different. We must maintain a high moral ground. We must set an example so the people will support us. We need to give them the confidence that when we free them from the yoke of “The House,” we won’t replace it with yet another unfair monopoly.

THE KID

But Mr. McSween, with all due respect, how can we expect to fight “The House” empty handed. Mr. Tunstall was unarmed and they shot him to pieces. You simply can’t fight guns with high sounding words. As for high moral ground, they started it. They have drawn the first blood. The people understand that.

McSWEEN

If we start killing for revenge, where will it stop? The people of Lincoln County want stability and peace, not disorder and violence. The only way to do this is to stay on the right side of the law.

THE KID

But Murphy and Dolan own the law. Sheriff Brady made out a legal warrant and organized the posse to arrest Tunstall. Brady’s got another warrant in your name. In other words, Mr. McSween, you’re next. We’ve got to get him before he gets you. It’s that simple.

Billy’s Blues

Billy’s Blues